Legal Entity Identifier (LEI) update: FSB global standardization efforts

April 6, 2012I recently attended the LEI Workshop conducted by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) on March 28 in Basel, Switzerland at the offices of the Bank of International Settlements (BIS). This workshop brought together representatives of many countries, agencies, organizations, financial institutions, and corporations from around the world.

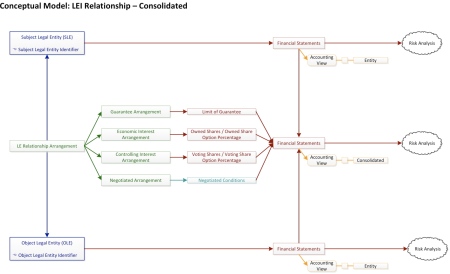

The FSB, as directed by the last meeting of the G20, is tasked with developing a global standard for the design, administration, allocation, and dissemination of a globally unique Legal Entity Identifier for use in, ultimately, all financial transactions. As businesses and corporations in all industries must conduct some degree of financial transactions in order to manage strategic assets or participate in currency and commodity markets, the impact and scope of the implementation of a global LEI transcends the financial industry, where the proposed use of a new global standard has obvious impact.

The FSB is in a bit of a ‘time-is-of-the-essence’ time frame window, spurred to make definitive progress on establishing a global mechanism for issuing LEIs due in part to (1) the fact that the CFTC has stipulated that swap derivatives dealers that fall under its regulatory auspices are to begin using an LEI this June and (2) the G20 has instructed that the FSB report on the formation of global LEI standards at the next meeting of the G20.

A full report on the numerous issues and alternatives that are occurring on both sides of the Atlantic with regards to converging on the business requirements and technical aspects of a global LEI system is beyond the scope of this update. I have prepared a more focused recommendation on a key aspect of the discussion regarding the use of the LEI code field and the concept of a federated approach versus a central approach to the establishment of LEI Registrars. That recommendation is attached as a PDF to this discussion topic.

I would urge you to review this proposal, as I do believe that it provides a means whereby ‘early adoption’ of putting an LEI process in motion by the CFTC can be harmonized with the FSB’s task of developing a specification and design for the implementation of a global LEI. It is quite important that the confluence of these two developments result in a productive and additive benefit to the financial industry (and global economy for that matter), as opposed to one in which the efforts clash and end up hobbling the benefits of establishing a global LEI while the compliance costs of supporting and participating in a global LEI system would no doubt remain undiminished.

The FSB has indicated that all comments and feedback as input to its deliberations must be submitted by April 16 in order for them to have a final report by the end of the month. I have submitted my attached recommendations to the FSB already, and I look forward to comments or questions from the community on this important subject.

Recommendation for LEI issuance via authorized federated registrars – rev 1-04

Apple Internet TV ? or, Google ?

August 28, 2011Apple Internet TV ? or Google ?

There is much speculation of the anticipated ‘next move’ of Apple, notably in the area of taking Apple TV to the next level, a la providing of Internet TV via the iTunes framework.

However, I believe that the real opportunity in the next disruptive wave of video, movies, TV, and the Internet is more likely to rest with Google, particularly with their acquisition of Motorola and the doorway to developing a truly Internet/TV integrated set top box.

This is because, in my opinion, the real breakthrough in both the Internet and cable TV programming is going to come when the full bandwidth of the broadband coax cable is used almost entirely for the Internet Protocol (IP) stack.

Currently, the broadband bandwidth of coax is inefficiently allocated and compartmentalized in frequency multiplexed video bandwidth slots for dedicated cable TV programming, with just a couple of such slots reserved for carrying IP traffic.

When the full bandwidth of coax is used to stream on-demand video via IP (and multi-casting so as to avoid duplicate streams for the same programming), the true convergence of the Internet and TV (and search, and clickable advertising, etc) will begin to be realized. Instead of offering the services separately, the real disruption will occur when the medium is integrated at the network, datalink, and wire level (levels 3, 2, and 1).

As others have pointed out, the Cable TV industry is not ‘hurting’ like the music industry was when Steve Jobs pulled 99-cent track downloads out of his rabbit hat. Google and Motorola can easily provide the technical means to integrate both content providers, broadcasters, ISPs, and Cable TV infrastructure sectors — but the business model of the existing Cable TV market providers will have to evolve and be attractive to the Cable TV franchise. The bandwidth of the Cable TV coax is so high that it will be a very long tme before competitive “last mile” delivery infrastructure (i.e., fiber) can reach the critical mass to replace or threaten coax.

The Cable TV providers see that long-term trend coming, and it will provide them with the incentive to work out new relationships with the consumer to bring new life into the existing coax network.

And can you imagine how the real consumer economy, and the advertising and marketing efforts of any and all manner of business, will respond when it is possible to integrate clickable Internet links on top of, superimposed, and synchronized with, video, movie, and TV programming of all kinds — including commercials, of course ?

It will be absolutely HUGE !

Byte-metered pricing rears its ugly head in the name of ‘net neutrality’

January 21, 2011The following is a critique in response to an article on Slate posted by a Farhad Manjoo, who tries to make the case that Internet pricing by the byte as opposed to by bandwidth is not only inevitable but preferable (or, at least, “reasonable”). Mr. Manjoo’s comments can be viewed here .

Mr Manjoo,

Your perspective is misguided and out-of-whack, as is your pronouncement of what rates seem “fair” or “reasonable”, for several reasons.

For starters, charging by the byte is more a measure of *storage* cost, and not appropriate to the concept and practice of streaming experience which the internet has quickly become — and for which the marketing and advertising promotions of the ISPs and Telcos are largely responsible !

Consider this: would you propose that the billing paradigm for cable TV be changed such that it is based on the amount of video information which is broadcast over cable channels ? It is quite easy to measure the amount of information bits contained in cable video transmission, and you could extend your rationale to suggest that viewers of cable TV programming have a certain allotment of total informational bits which they can consume in a month, and which they must budget, lest the charges for the service be escalated. If you watch too much TV and exceed your allotment, you pay more.

When you elect a cable TV selection of programming, the assumption is that you can ‘watch’ that programming as much as you want in any given month in exchange for the monthly charge. In other words, the contract is based on agreeing to pay for a given level of streaming, always on, experience — not the number of video bits which are pushed down the cable.

With regards to connectivity to the Internet, if an ISP quotes a certain level of bandwidth/time (e.g., 5 Megabits/sec), that is the value proposition which a consumer elects to pay a certain amount for on a monthly basis. Lower bandwidth is lower cost, and the quality and capabilities of the informational or media experience changes according to the bandwidth elected.

Consumers have no clue as to how many bytes it takes to render a particular web page, nor how many bits are being streamed to provide a given level of audio or video resolution. That is a completely foreign value proposition for the contemporary Internet consumer, and your estimations of how many ‘bytes’ are reasonable represents both a static and irrelevant measure of what a consumer is expecting to pay for.

I am not suggesting that consumers be given ‘infinite’ bandwidth for a fixed cost, mind you, and I certainly recognize that per-user bandwidth quotations of quality of service has a significant total network infrastructure capacity requirement and expense. But charging by the byte as a means to somehow reconcile total system bandwidth with aggregate consumer demand is bass-ackwards, and guaranteed to ultimately cause dissatisfaction and disruption of both consumer demand as well as impair the continued growth and expansion of the entire Internet-based economy.

Charging by the byte simply offers the ISPs and Telcos the ability to continue to grow revenue without concomitant improvement and investment in Internet infrastructure, and turns the Internet into a fixed utility of bandwidth-capped pipes appearing to deliver a finite, consumable resource like water or natural gas, as opposed to the far more unlimited ability to simply move electrons or photons back and forth at will without exhausting the bits, or needing to ‘store’ them.

What the ISPs and Telcos need to do is simply quote bandwidth at a rate that they can deliver to the growing population of consumers, and use the growth in consumer volume as the source of revenue to fund ongoing capital investment in infrastructure and total system bandwidth to meet the growing aggregate demand. LOWER the continuous bandwidth per time per user if need be in order to accommodate supplying continuous bandwidth at that level of service to the customer population ! Charge more for higher bandwidth, yes, but do NOT quote ultra-high-speed bandwidth for a rate which the infrastructure can not support, and which would force you into ‘metering’ out the total bandwidth in a piecemeal, non-continuous, and potentially interruptable service based simply on number of bits or bytes.

Your estimation of what is ‘fair’ or ‘reasonable’ in terms of bits or bytes per month is totally unfounded, would lock in a fractured and fragmented Internet experience calibrated at current levels of capabilities, and would proceed to make that capped experience subject to outages and interruptions based on unexpected budget constraints as underlying amounts of data for certain types of services would necessarily evolve.

You display your most egregious lack of appreciation of what the Internet is really about with the following comments:

And say hooray, too, because unlimited data plans deserve to die. Letting everyone use the Internet as often as they like for no extra charge is unfair to all but the data-hoggiest among us—and it’s not even that great for those people, either. Why is it unfair? For one thing, unlimited plans are more expensive than pay-as-you-go plans for most people. That’s because a carrier has to set the price of an unlimited plan high enough to make money from the few people who use the Internet like there’s no tomorrow. But most of us aren’t such heavy users. AT&T says that 65 percent of its smartphone customers consume less than 200 MB of broadband per month and 98 percent use less than 2 GB. This means that if AT&T offered only a $30 unlimited iPhone plan (as it once did, and as Verizon will soon do), the 65 percent of customers who can get by with a $15 plan—to say nothing of the 98 percent who’d be fine on the $25 plan—would be overpaying.

The Internet is NOT a storage device ! And your assessment as to what constitutes reasonable ‘use’ of the Internet, based on current usage (and justifications by AT&T ! ) is backward-looking. You might as well be saying that, because 98 percent of the population “gets by” with wagons pulled by horses, there is little need for the horseless carriage ! That is sooo 1890 !! Best to look ahead to the future, not in your rear-view mirror.

You need to rethink your concept on Internet billing, or you will soon find yourself in the position of needing to calculate the equivalent of how far you can drive on a fixed battery charge in any given month.

BAD IDEA !

A Unique Opportunity for a Win-Win in Financial Risk Management

November 25, 2010Seeking to manage, or at least measure, financial and systemic risk by a closer inspection, analysis, and even simulation, of financial contracts and counterparties at a more precise level of detail and frequency is a significant departure from many traditional risk management and supervision practices.

The results of more detailed contractual and counterparty analysis — which, taken together to reach the level of the enterprise from the bottom up — offers far better insights into the risk dimensions of both a firm, as well as the financial system, than practices in the form of large-brush composite risk measures and coefficients applied to balance sheets from the top down. The latter greatly reduces the burdens of compliance and regulatory reporting, but it is also much less informative and accurate.

The goals and objectives of accounting practices and methodologies are generally to provide an accurate view of the financial condition and activity of a firm as a going concern, to the extent that one-time events are noted as exceptions, and the effects of other transactions such as capital investment, revenue recognition, and depreciation are spread across a wider horizon of ‘useful life’.

When accounting methodologies aimed generally at showing a longer-term view of a firm’s ‘trailing average’, or smoothed-out, behavior are applied to risk management, artifacts can arise that obscure or mask risk, and the one-time events which accounting practice seeks to footnote should in all likelihood be headline topics for risk analysis such as stress testing.

Some fundamental premises of how best to respond, as a firm and as an industry, to regulatory requests for more detailed contractual and counterparty information:

1) Individual firms should seek to turn what is traditionally viewed as a non-productive overhead cost of regulatory reporting and compliance — in light of the new mandate to provide more detailed financial information — as an opportunity to map contract-level financial positions into a financial data repository that spans the entire balance sheet (and off-balance-sheet) of the firm and allows across-the-board analysis and stress testing using level-playing-field scenarios and assumptions.

Currently, most firm’s product divisions are isolated in operational silos with proprietary systems-of-record formats and potentially incompatible risk management methodologies and assumptions. Implementing this approach will result in risk measurement and management practices which are more timely, more comprehensive, and based on higher-resolution detailed data — a ‘win’ for the firm.

Firms should not view the proposal to create and populate such a database as an attempt to jack up their entire financial operations and insert a new ‘ground floor’, nor to be a replacement for internal data warehousing initiatives. Rather, the model is to allow an interface database to be populated with appropriate mappings from existing systems within the firm.

As such, such a database, though comprehensive and more detailed than traditional G/L reporting data stores, is not ‘mission critical’ , but more along the lines of decision support — and could provide a platform for productive use to that effect internally within the firm as well.

2) The industry as a whole, in conjunction with regulators, should strive to agree on a common standard to represent low-level financial positions and contracts such that each firm does not create its own proprietary version of such a data model, one which then requires further re-mapping and translation (and likely incompatibility) at the level of systemic oversight.

Having the financial industry and the public regulators agree on a common data model, with requisite standardized reference data, will be a “win” for the public good as well, as it will greatly reduce the cost and complexity of making sense of more detailed financial information for purposes of analysis at the systemic level in the Office of Financial Research.

Finally, by implementing a form of distributed reporting repository, if you will, each institution can make the database available on a secure basis to not only regulators but also to internal staff as well as vendors who can supply value-added reporting and analysis tools predicated on the standard model. This is yet a third win for economic efficiencies that would make available better risk management practices to a wider range of institutions who otherwise would not choose or be able to develop such tools.

The increased regulatory requirements mandated by the recent passage of the Dodd Frank Act are no doubt not a welcome development for financial institutions, and the challenges to fulfill the specific functions of the Office of Financial Research as delineated therein would be formidable even with full cooperation from the industry. However, given that the work needs to be done, and time and effort expended, it clearly is in the best interests of the financial industry and the public if the projects can be pursued in a manner that will produce substantial long-term benefits to offset the additional costs incurred.

Systemic Risk Data Challenge and the Office of Financial Research (OFR)

November 23, 2010The Internet

August 23, 2010

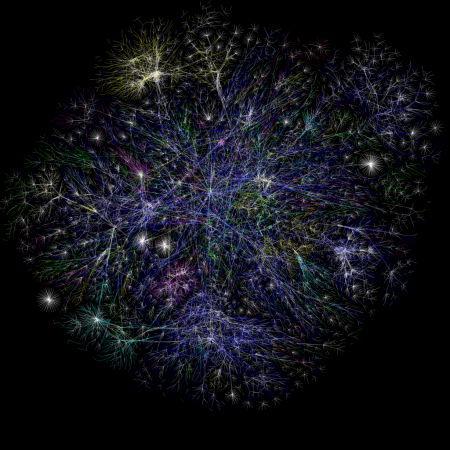

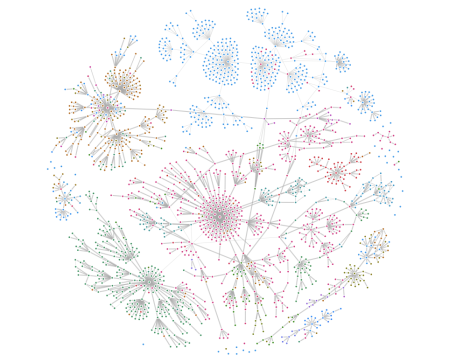

The Internet, from 50,000 feet - courtesy http://www.opte.org/maps/

“Net Neutrality” does not mean “equally fast, everywhere”

August 22, 2010“Net Neutrality” means too many different things to different people.

For example, concerns about the potential for discriminatory practices by ISPs or telcos based on content, application, or identities or affiliations of content consumers or producers are usually conflated with simplistic observations about the need for ‘equal speed’ being a necessary condition for net neutrality.

Al Franken discusses issues and concerns related to competition (or sufficient lack thereof), but he too raises the ‘speed equality’ notion as a requirement for ‘free speech’ on the internet.

It is safe to say that 99% or more of the public does not understand how the Internet works, or for that matter how computers attached to the Internet work. Discussing legitimate concerns about non-discriminatory processing of Internet traffic in simple terms of speed only further confuses the public, and create political responses for the wrong reasons.

What we all agree on is NOT the issue

What is not to be tolerated in any scenario, ‘network neutrality’ or not, is discrimination based on type of protocol, or content, or application, or content provider, or consumer.

It is this type of discrimination which has vociferous proponents of ‘net neutrality’ most up in arms, and yet it is not the type of discrimination that is likely to ultimately be the real net neutrality issue, for the simple reason that it is and will be easy for everyone to agree that those forms of discrimination are inappropriate, anti-competitive, and, yes, illegal.

The Need for Speed

Unfortunately, it is “speed” discrimination on which simplistic overtures to net neutrality are based.

For example, the following from the recent op-ed by Al Franken on the subject:

An e-mail from your mom comes in just as fast as a bill notification from your bank. You’re reading this op-ed online; it’ll load just as fast as a blog post criticizing it. That’s what we mean by net neutrality.”

This definition of ‘net neutrality’ — that every interaction is “just as fast” as any other, is the most dangerously misleading of all attempts to define (and, in Senator Franken’s case, legislate) ‘net neutrality’.

If, by his comments, Senator Franken means to say that “the rate at which bytes are transmitted over the network, for consumers sharing the same level of cost for the same level of quality of service, should be the same”, then yes — (that is, definition #3 of ‘net neutrality’) — and is perfectly reasonable.

But the imprecise language of the appeal to ‘equally fast’ will incorrectly lead people to believe that net neutrality is intended to make the time it takes to download Avatar equal to the amount of time it takes to send a tweet, with the further stipulation that this be via terrestrial or wireless connections, and all for the same cost as the least demanding of levels of service.

Where “Net Neutrality” really applies is in the requirement to not discriminate based on content. This includes, of course, any selective slowing down of traffic based on application or protocol from sources who have paid the same for the same bandwidth. Local ISPs (notably cable companies with their claims of 5MB/sec and more bandwidth) need to be able to support those promises, or else not promise so much — truth in advertising, quite simply.

The “15 Facts” infographic

ReadWriteWeb has posted an ‘infographic’ entitled “15 Facts About Net Neutrality“.

The 15-point summary covers ‘bullet points’, but does not provide sufficient insight into the not-so-obvious distinctions among definitions of ‘net neutrality’.

In particular, the ‘3 definitions of net neutrality’ makes a stab at this, but more attention needs to be focused on specifically and exactly what is being talked about when different folks debate ‘net neutrality’.

To recap, the ‘3 definitions of Net Neutrality’ provided by the Online MBA Programs folks are:

1. Absolute non-discrimination:

No regard for quality of service considerations

2. Limited discrimination without QoS tiering

Quality of service discrimination allowed as long as no special fee is charged for higher quality service

3. Limited discrimination and tiering

Higher fees for quality of service provided there is no exclusivity in contracts

The definitional hole in the above summary points is simply: what is the domain potentially being discriminated? Is it content type ? application ? protocol type ? bandwidth ? consumer ? content provider ?

Definition 1 is, for the most part, the hue and cry of the status-quo, and is bound to run into trouble with consumers at some point.

This will occur when the volume of internet traffic of a (growing) minority of highly active internet consumers reaches thresholds where it taxes the bandwidth and capacity of Internet service to the point that a majority of less-active consumers are noticeably and negatively affected.

For example, when a sufficient volume of constant bit torrent traffic — or a sufficient increase in the amount of video-on-demand being streamed — reaches a level where local delivery is saturated or visibly impacted, consumers will notice (and ISPs and telcos will seek to maximize the number of satisfied, paying customers). This is what started the whole issue, after all !

Definition 2 would appear to be the worst of all worlds. “no special fee … charged for higher quality service” would of course never occur in a bandwidth-challenged network. Quite the opposite – that definition is absolutely equivalent to: “same fee charged for poorer quality service” ! It would let ISPs degrade service (or simply let service degrade on its own). This is the least desirable scenario.

Definition 3, which acknowledges that higher quality of service (translation: continuously available higher bandwidth) is something which consumes more of the capital infrastructure resources of the supply chain (ISP and backbone) — and for which a higher cost is appropriate — would seem to be a reasonable starting point for network neutrality that guarantees equal access within a given quality of service.

Unfortunately, this definition is one which is also drawing considerable flak over the concern that it will create two classes of internet users: “rich” and “poor”, or “fast lanes” and “slow lanes” (See the transcript of Cali Lewis’ interview on CNN, for example).

Until the language and conversation regarding ‘net neutrality’ is cleaned up and made more precise, the controversy will continue to swirl unproductively. And can you imagine the provisions or effect that Congressional legislation — in the absence of such specificity, and in the presence of such fuzzy emotional appeals — will have ? It certainly will not have the desired effect !

If, for example, a clumsy, and poorly thought-out, knee-jerk legislative reaction results — one which is too restrictive or onerous — then the result could be one where growth and competition to provide higher bandwidth service is replaced by a strategy on the part of ISPs and telcos to simply start charging more by the data byte with minimal investment in technical infrastructure. This outcome would ultimately cost all consumers more, and for less service !

Is Internet capacity a “non-issue”, and equal bandwidth a “right” ?

August 21, 2010Here is the link on CNN to the 5-minute segment: Cali Lewis / Max Kellerman discuss Net Neutrality

A transcript of the interview follows. After watching the discussion with some interest, I tweeted Cali with a brief comment that she had made a statement about technology and capacity which was misleading and very much in error. I later received a reply from her producer, Dave Curlee:

remember that CNN has a VERY broad audience. Network TV doesn’t like technical detail… keep it simple…..

…. Net Neutrality is a HUGE subject. a 5min segment can’t do more than ‘maybe’ give a 50k foot view.

Dave is quite correct, of course. However, the fact that network TV “doesn’t like technical detail” is not a sufficient reason to gloss over certain aspects of technical realities in a manner that is fundamentally incorrect.

Now, I quite like Cali’s engaging style and friendly charm, and I can see why she is understandably popular as a source of information about technology, in particular to an audience who may not be all that technically literate. But the “Net Neutrality” issue is quite pivotal, and the role of “translator” of the issue quite important as well.

The Net Neutrality issue has economic, technical and social dimensions. Cali does a good job in addressing the social aspect of the issue, but, unfortunately, the technical dimension was not as well served.

Reading the transcript will no doubt reveal where some of the oversimplified (and misleading) technical statements are made. I am posting the transcript now without comment or analysis, choosing to follow up with that after presenting the interesting and revealing interview first.

I trust that Cali will understand that my desire to engage her on some of her statements is a constructive effort to improve and advance the dialog and understanding of this important issue, and I salute her for being willing to step up and discuss the topic live on air.

Transcript of the interview

MK: Explain what we are talking about here … “net neutrality”

CL: It is a heated topic, as you saw from the clip, everybody gets really up in arms about it, so … “net neutrality” says that carriers treat all Internet traffic the same, um, when data is requested, it’s just sent out, it’s not sped up, it’s not slowed down, it’s just “sent”. Now, there are certain companies that have, let’s say, special needs, but they have private networks, so it’s not being affected, or worked into the open Internet. Now…

MK: OK, so why would changing the rules be so bad, you know, what would that change ?

CL: Well, so what we’re talking about here is that the companies that own the fiber that we use to connect to the Internet, they’re wanting to be able to prioritize traffic, so essentially they’re wanting to take money from people who can afford it, which leaves the little guys out in the cold, and I’m sitting here thinking, this sounds a little bit like extortion to me.

MK: Cali, I mean, in terms of the speed with which you get stuff and the payment for it, when you went from dialup service to high speed you had to pay more for high speed, and it got you the information faster — what’s the difference ?

CL: Well, we’re not talking about an increase in , in technology here, we’re talking about prioritization of the Internet, and so it’s a totally different beast. So the other side, the people who are against “net neutrality”, what they say is that the traffic is increasing exponentially, and we have a finite amount of capacity and something has to give somewhere somehow, and so that they have to be able to prioritize traffic. Well, it’s just a flawed, um, fundamentally flawed argument — let’s take an example here, and I know it’s silly, but I brought a prop (laughing, holding up a 10base-T ethernet cable). You know the ethernet cable, right ?

MK: right

CL: so, the ethernet cable, it went from, you know, 10 megabits to about a gigabits in about ten years, so …

MK: so how many “megas” in a “giga” again ?

CL: (laughing) a thousand ?

MK: ok, so it’s a thousand times faster in ten years

CL: ok, so …

MK: a giga is a million … or a billion …

CL: (laughing) right, right … and so it went … (laughing) we don’t have to get into the math, right ? And so it’s a huge amount of, um, of capacity that’s changed, and the actual cable has not changed …

MK: so in other words it’s not about the hardware, it’s about the technology, and your argument is that the technology will catch up to demand in terms of the packets of information that are sent back and forth. OK, here’s —

CL: Exactly. It’s about what happens on the ends, and there are companies that are working to make all of that work, and we don’t need to worry …

MK: Let me ask you something — I understand as a consumer that I like the idea of “net neutrality”, right, because I want everything to be treated equally, I love this system that we have of the Internet where you can get information from anywhere, and it’s not prioritized, it’s wherever you want to go … on the other hand … it seems to me analogous in a way to software companies, when Bill Gates was a young man, and the culture which had come out of these software geeks was such that, you know, you just shared it and everything, and Bill Gates was saying “no no, wait a minute, I invested all this money in my software, you gotta pay for it, I’m not just sharing it with everybody” and [he] made a ton of money and reinvested that money and maybe sped up the development of software, one could argue. So is your argument that the public utility should trump private interest, simply, in this case ?

CL: Well you know the Internet is … this is really a philosophical question more than a technical question, or whether it’s ok for … we’re talking philosophically here, in what your question is proposing. Is the Internet a right to everyone ? Is it important that equality is on the Internet ? Is it important for people to be able to, you know, poor people to be able to drink the same clean water that rich people …

MK: Except that it’s like printing books, and the telephone, and the television — none of those things were “rights”, right ? Why is the Internet … In other words, this culture has grown up around us, so we’re used to it. Who is to say that that necessarily means that it should stay that way ? I’m trying to come up with the strongest devil’s advocate position that I can.

CL: (grinning) I know … and it’s going to be SO hard for you, because … (laughing) … the Internet is a “right” now, you know, it wasn’t … before the Internet existed it wasn’t a right, but it became available, and it is essentially a right at this point in time it is part of all of our lives. It is world-wide communication that opens up so many possibilities. For example, my show [ geekbeat.tv ] was not possible before the Internet existed because everything was controlled by TV networks, radio, newspapers, but now I have the ability to communicate world-wide, and have a very large audience, um, but now we’re talking about the fact that CNN.com could pay more than me, and you know be able to kind of push me down, and, uh, it IS a “right” now …

MK: Cali Lewis thank you, we’re running out of time, but thank you very much for your explanation here, I thank you for your time, thanks for coming on

The Fuzzy Semantics of “Net Neutrality”

August 14, 2010For all the legitimate and significant issues regarding the future evolution of the Internet which the term “Net Neutrality” is meant to embody, the phrase would appear to have become a bit of a conceptual chameleon with a life of its own, and whose meaning is not particularly clear — certainly not to many people when they first encounter the notion.

Despite the fact that the events and practices which instigated the initial debate are fairly specific, the term has become the distilled cornerstone for a veritable uprising against telcos and ISPs, carrying with it a cachet which is nearly on the level of “freedom of speech” and “human rights”.

When combined with the simple lead-in of “those in support of …”, the term “net neutrality” suggests an air of impeccability, its own “self-evident truth” and standard bearer for a cause which all intelligent and righteous beings should without question support. For that catchy spin alone, whoever coined the term deserves an advertising Cleo award.

But the fuzzy semantics of the term “net neutrality” can be misleading and lead to confusion or distortions in attempting to analyze or discuss the multi-faceted and non-trivial issues and trade-offs which are teeming immediately beneath the self-assured surface of that simple label.

A case in point

For example, in a recent TechCrunch column, MG Siegler writes:

“For net neutrality to truly work, we need things to be black and white. Or really just white. The Internet needs to flow the same no matter what type of data, what company, or what service it involves. End of story.”

Now that is quite a remarkable statement, if you think about it. With apologies to Mr. Siegler for selecting his statement as the guinea pig in this lab experiment, let’s analyze the statement a bit more closely.

In a very short space of words, this statement contains such phrases as “truly work”, “we need things”,”black and white”,”just white”, and “flow the same”.

Ignoring for a moment the absence of a clear description of just what “net neutrality” is that we should be trying to make “truly work” (the assumption is that we all know, of course), the statement that follows which seeks to define just what is required for that to happen is remarkably vague and imprecise. In fact, it is more emotional than logical, and — in tone, at least — resembles the kind of pep talk a coach might give to his team before they take the field in a sporting contest.

In fairness, “we need things to be black and white” alludes to the fact, which no one would deny, that the rules, policies, practices and terms of service of ISPs vis-a-vis their customers should be just that — transparent, clearly documented and understood, i.e., black and white.

The transition to “or really just white” is to say that these rules and policies should not create discriminatory distinctions among customers or types of service, bifurcating them and their respective internet access into two classes: “legacy” and “future”, rich or poor, first class or coach, i.e., black or white. That is a clever segue and turn of phrase.

Caution: thin ice ahead

Where Mr. Siegler runs into some significant thin ice is when he follows with “The Internet needs to flow the same no matter what type of data, what company, or what service it involves.”

This statement may well appear to most people to be an adequate, if not altogether necessary and sufficient, definition of “net neutrality” — but perhaps therein lies the rub with the truly fuzzy semantics of the term.

To be clear, there is no quibble with the “no matter … what company” part of the statement. The most compelling part of the criticisms leveled at ISPs has to do with their documented use of ‘discretionary policies’ to ‘manage’ Internet traffic and the natural concerns over the potential abuse by ISPs of the inherent power and leverage which comes with being in the position of being the gatekeepers of the Internet.

Discriminatory practices by ISPs, including preferential treatment of customers or partners, whether for commercial or even political purposes, would clearly be improper, and have a negative effect on the innovation and economic growth which the Internet fosters and enables, particularly when the ISPs involved are “size huge” and affect millions and millions of customers.

Go with the flow … but fasten your seatbelts

Rather, it is in the declaration that the “Internet needs to flow the same no matter what type of data … or what service it involves” where major turbulence in the “net neutrality” debate is encountered, requiring that we fasten our seatbelts for the duration of the flight, as it were.

It is at this point in our journey down the rabbit hole where the matter of ‘net neutrality’ becomes more turgid, yet multi-faceted, and without clear solutions — not ‘black and white’ ones, and certainly not ‘just white’ ones.

The phrase “flow the same” is where the devil indeed lurks in the details, cloaked in that larger statement which, for all intents and purposes, could well have been crafted by tireless opponents of discrimination in the U.S. Civil Rights movement.

What exactly does “flow the same” mean, and what are the implications of any of its possible interpretations ?

Picky, Picky

Before proceeding, you may be asking “why so picky”. Rest assured, I am not defending, nor am I a shill, for telcos and ISPs in this debate ! And I am just as concerned as the next person about establishing any precedents or slippery slopes that would lead to the bifurcation and balkanization of the Internet.

But to demand that the “Internet flow the same” regardless of data or service is not only completely ambiguous, it is also a notion with inherent contradictions along multiple dimensions.

In an effort to explore the problems that the fuzzy semantics around this particular notion entail, let’s do some “thought experiments”. Lab coats and protective eye goggles ready ?

Thought Experiment

In this “thought experiment” , let’s take two scenarios, or snapshots, if you will, of two possible alternative internet universes.

Alternate Internet universe 1.A

Alternate Internet universe 1.A (AIU 1.A) consists of one thousand servers and one billion clients. The principle service in this alternate universe consists of sending and receiving short messages, called “Burps”.

- Clients poll all 1000 servers for Burps addressed to them, evenly spread out over the course of repeated 60-second intervals.

- When a client contacts a server in the course of this polling, a client can retrieve all Burps in their Burp inboxes, respond to or acknowledge Burps retrieved in previous polls, and also post, or deposit, one new Burp of their choosing at each server.

- Finally, Burps are limited to 100 bytes.

Let’s analyze the total “Internet flow”, in terms of both bytes and bandwidth, of this alternate Internet universe across the entire network, shall we ?

The maximum utilization of Internet 1.A occurs when every client posts one new Burp at each of the 1000 servers every 60 seconds, and responds (with a reply Burp) to all Burps retrieved from any and every server at the time of the poll of each server 60 seconds previously.

Remember, the rules of this universe specify that clients can only deposit one Burp per server when they check that server for queued Burps every 60 seconds.

Even though some clients may retrieve many Burps from their inBurp queue, others clients may have none to retrieve.

The steady-state bandwidth per second of universe 1.A in maximum utilization (calculating the total amount of information processed by the network in a 60-second cycle with all clients performing to maximum capacity, and then dividing by 60) in bytes/sec is therefore

[ #clients X #servers X bytes/burp X 3 ] / 60

The factor ‘3’ above is due to the fact the number of burps per client per cycle can be analyzed thusly:

- each client can respond to each retrieved burp (1) with a response burp (2) as well as post a new burp (3), and

- because every client is constrained to posting only one burp per server per polling cycle, the statistical aggregate amount of burps which flow through the Internet of alterrnate universe 1.A is steady-state bounded and enumerable, regardless of the distribution of different number of burps in the queues of different clients.

Plugging in the numbers in the expression above, we get:

[ 1 billion X 1 thousand X one hundred X 3 ] / 60, or

5 x 10 ^ 12 bytes/sec = 40 x 10 ^ 12 bits/sec

Alternate Internet universe 1.B

Alternate Internet universe 1.B has the same number of clients and servers as AIU 1.A. However, the type of data and service provided in AIU 1.B is different than that of AIU 1.A. Alternate Internet universe 1.B provides realtime Channel-Multiplexed Multimedia Stream (CMMS) sharing among all clients.

- Each channel-multiplexed multimedia stream consists of any number of different individual media streams on different virtual channels of the single multiplexed stream, as long as the total allowed bandwidth of the a channel-multiplexed media stream is not exceeded.

- The individual media channel streams are multiplexed together into a single CMMS solely in order to simplify the transport-level management and routing of media channel stream sharing between client and server nodes across the network.

- Each client can stream exactly one CMMS to each server, and can choose to subscribe to up to 1000 multimedia channel streams across the population of servers.

- Clients can choose to subscribe to more than one CMMS to a single server.

- Furthermore, the up to 1000 CMMS which clients can stream to each server can all be unique.

- The maximum bandwidth of a single CMMS, fully compressed after being multiplexed and ready for transmission, is 1 Gigabit/sec

What is the information bandwidth of AIU 1.B at maximum utilization?

This is fairly easy to calculate, because, when each client node operates at capacity, 1000 CMMS streams are originated, and another 1000 are subscribed to and received. If we furthermore assume that every CMMS is unique and remove systemic opportunities for multicasting or redundancy optimization, we arrive at

#clients X CMMS-maxbandwidth X ( #maxstreams-out + #maxstreams-in )

or

1 billion X 1 Gigabit/sec X 2000 = 2 X 10 ^ 27 bits/sec

Kind of Blue (i.e., “So What”)

Each of these alternate Internet universes have the exact same configuration of clients and servers — and one could have been instantaneously cloned from the other (theoretically speaking) by some sleep-deprived string-theorist-in-the-sky who fell asleep and whose head lurched forward and accidentally hit the ‘Big Universe Morph Process (BUMP)’ that-was-easy button in the middle of a DNS root node upgrade …

If we compare the total system bandwidth of Alternate Internet universe 1.A with that of Alternate Internate universe 1.B, the system bandwidth of AIU 1.B is 5 x 10 ^ 13 times greater than that of AIU 1.A.

That is not merely 10 ^ 13 more data in the network (a pittance). No, it is a 13 orders of magnitude (powers of 10) difference in BANDWIDTH . AIU 1.B is has over 10 Billion times the bandwidth of AIU 1.A, or, put another way, it would take 10 Billion AIU 1.A entire networks to equal a single AIU 1.B network.

Miles and Miles to go before we sleep

The two Alternate Internets have, yes, different data and services. Yet according to the definition of the fundamental principles of ‘Net Neutrality’ so succinctly stated above, “The Internet needs to flow the same no matter what type of data …or what service it involves.”

Alternate Internet universe 1.B would of course have no trouble ‘flowing the data’ of AIU 1.A. But obviously, if the tables were turned that would not be the case at all.

At this point in the infancy of the Internet, we are certainly farther along than 1.A, but nowhere near 1.B — perhaps more like 1.A.2.0. And we are already mixing in a bit of 1.B ‘beta’ into the 1.A.2.0 ‘release’.

In fact, the T3 backbones look a lot like bundles of the ‘CMMS’ multiplexed media channel streams conjured up above. And we have billions of Internet clients ‘burping’ in various flavors of social networks at the same time that businesses are offloading proprietary IT shops to “clouds”, consumer e-commerce is looking for that “next big thang” ahead of Web 3.0.

Meanwhile, the wireless data revolution is, well, kind of bringing the wireless network to its knees just as the first generation of hand-held “pre-CMMS” streamers are being introduced and fanning the flames and whetting consumer appetites and expectations with dreams of sugar plums and voice-controlled robot candy canes.

Here comes the Q.E.D.

It is perhaps the not-exactly-the-same zone of mobile wireless Internet that is the most incontrovertible evidence that the fuzzy semantic “same flow no matter what” notion of ‘Net Neutrality’ is inappropriate, and an overly simplistic star to hitch your Internet wagon to. As a ‘thought experiment’ exercise at the end of the chapter, consider doing an analysis of pushing out the envelope of the Internet Universe in which the terrestrial zone of the Internet grows exponentially in bandwidth because of the essentially unlimited ability to simply lay more and more pipe to do so. Terrestrial pipe has the following magical property: it is truly scalable and bandwidth-accretive, because adding another pipe does not interfere or detract from the pipes already in place.

This just in, in case you did not get the memo: the wireless spectrum, regardless of how cleverly it is compressed, has some theoretical bandwidth limits. Why ? because, by its very nature, it is just one big “pipe in the sky” which is shared, and ultimately contested, by everyone in the geographic area within the cone or zone of the immediate local wireless cell.

When the analog voice cell network upgraded itself from 3-watt phones to 1-watt phones, way back in the oh-so-nineties, the wireless network transitioned from larger area cells to much smaller cells. The main objective was simply to be able to increase the density of mobile subscribers per area and thereby allow a large increase in the total number of wireless subscribers system-wide. The auction and re-purposing of electromagnetic spectrum by the FCC, making more spectrum available to the wireless industry, is a welcome, but ultimately finite, addition of bandwidth and headroom to the wireless space. And, as we all know, for every headroom, there is a max.

All you need to do is extend out the timeline sufficiently, and you will (likely sooner than we think) reach the point where the growth in wireless bandwidth is again constrained, and we ultimately run out of road.

The only strategy which will mitigate the trend to saturation of bandwidth within a given size cell and a given fixed spectrum is the same one described above regarding the first mobile analog voice cell network. Namely: reducing the effective size of the cell so that the exponentially increasing bandwidth of the terrestrial Internet can, by extending its tentacles and hubs into a larger number of lower-energy spaces, make more bandwidth available to a smaller number of users but in a much larger number of micro-cells.

This strategy, or one very similar to it, will be required to continue expanding and improving the performance, reliability, availability, and bandwidth of the wireless domain for a simultaneously growing population of consumers, types of data, and services.

But to think, maintain, or imagine that the amalgamation of terrestrial and wireless interconnections to the Internet will “flow the same”, no matter what type of data or what service, is merely a recipe for ongoing angst, disappointment, and internet class warfare, in my opinion.

Chocolate or Vanilla ? or … Coppa Mista ?

Yes, we must collectively find our way, with consumers holding the feet of both content-providers and ISPs to the fire by voting with their feet in a robust and competitive market economy.

It is the factors which impede and interfere with the power of consumers – individuals and businesses alike — to collectively and competitively shape the outcome of the next wave of the Internet’s evolution which are the real issues and dangers that threaten the prospects on continued survival and prosperity of an innovative and open Internet.

It is not quite as ‘black and white’ (or chocolate and vanilla) as saying that the ISPs (and their purported Vichy Regime collaborators) are wearing the black hats while the rest, actively championing ‘Net Neutrality’ (whatever that really means ultimately), are wearing the white hats.

The fuzzy semantics of just what “Net Neutrality” is thought to be are not necessarily helping, either, despite the critical importance of the issue, the debate, and what happens next.

You must be logged in to post a comment.